Table of Contents

After being diagnosed with Crohn’s disease I spent a lot of time researching the science of gut health and what we can do to build a healthy microbiome.

This is what I found.

🍏 How the Gut Works

What is the Gut?

The gut is an intricate system of organs, muscles, and bacteria, which is primarily designed to break down the food we eat into nutrients.

Our body then uses these nutrients to store energy, build important biological structures, and keep us healthy.

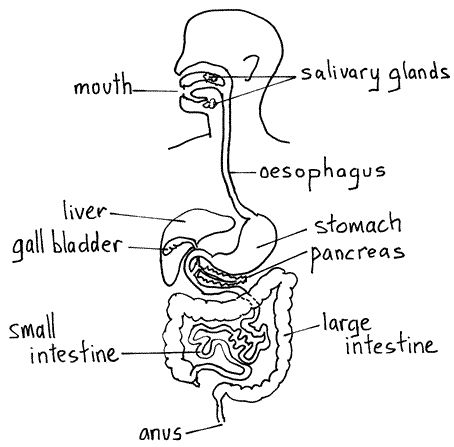

To do this effectively, the gut relies on a long and complex pathway called the digestive tract – a muscular tube that starts at the mouth and ends at the anus. Along this path, food is chewed, mixed with enzymes and acids, absorbed into the bloodstream, and eventually passed as waste.

Each section of the digestive tract has a specific role to play in this process:

- The Mouth: Digestion begins the moment food enters your mouth. Salivary glands release enzymes that break down starches, while saliva (rich in calcium and antibacterial mucins) helps protect your teeth and kill harmful microbes. Meanwhile, your tonsils act as immune sentinels, filtering out pathogens and training your immune system to distinguish between good and bad bacteria.

- The Oesophagus: Once you swallow, food travels down the oesophagus. This is a muscular tube that uses wave-like contractions (called peristalsis) to push food into the stomach.

- The Stomach: Your stomach produces acid before food even arrives, breaking down its molecular structure. It then churns the contents for hours, mixing acid with food to create a partially digested pulp known as chyme.

- The Small Intestine: This is where most nutrient absorption happens. Digestive enzymes from the liver and pancreas further break down chyme. Then, tiny structures called villi and microvilli absorb nutrients into the bloodstream or lymphatic system. Carbs and proteins head to the liver via blood, while fats take a detour through the lymph system before being processed.

- A short while after digestion, leftover food is flushed through the small intestine in a cleaning wave, producing the familiar growling sound known as borborygmi.

- The Large Intestine (Colon): The colon digests leftover particles the small intestine couldn’t handle and slowly reabsorbs water and electrolytes. Most of your microbiome resides here, extracting the final nutrients and supporting overall health.

- Attached to the large intestine is the appendix, which helps store and repopulate healthy bacteria, especially after illness or diarrhea, and contributes to your immune defense.

- Poo: Finally, waste that can’t be digested is passed out of the body. Pooping is a highly coordinated process, involving a negotiation between your internal and external anal sphincters. Your brain decides when it’s time to release based on signals from these muscles.

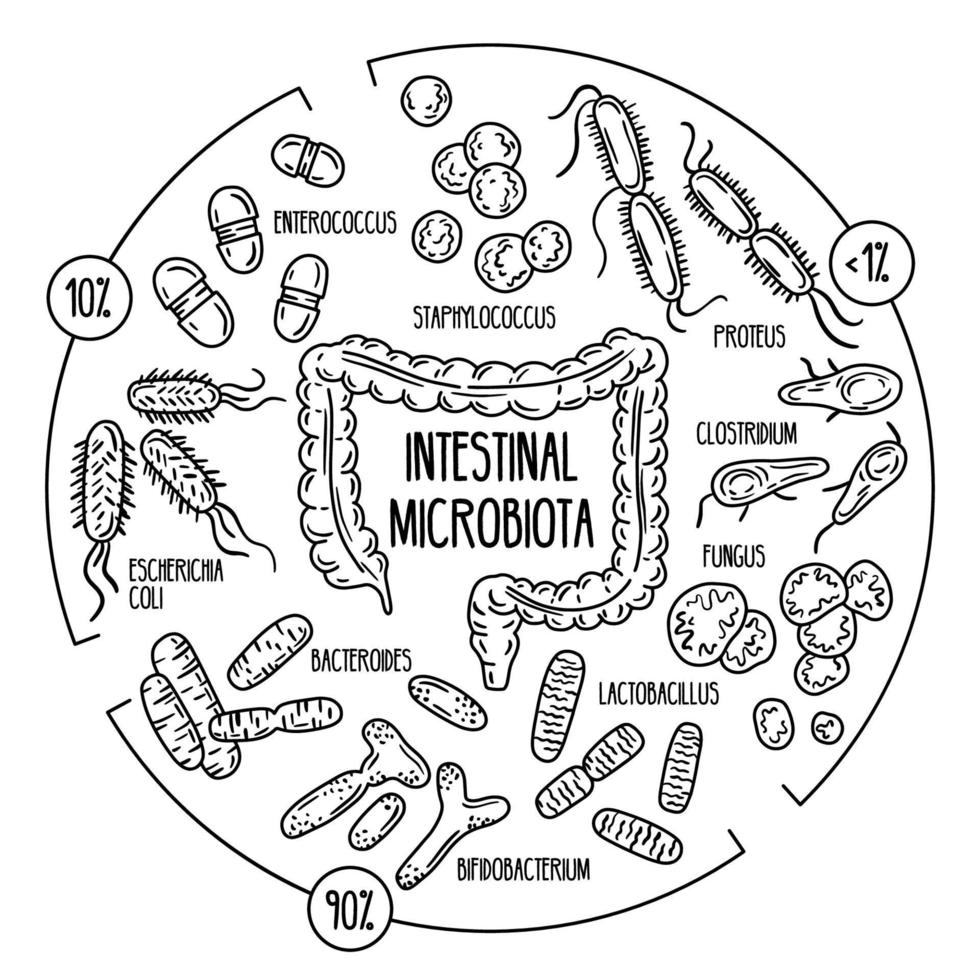

The Microbiome

We have a huge population of bacteria that live in our gut, which strongly influences the way our body works (including our metabolism, immune system, and brain function).

This is our gut microbiome.

A healthy microbiome is diverse and resilient, meaning it has a wide variety of microbial species (bacteria, fungi, viruses, etc.) and recovers quickly from disturbances (such as illness, antibiotics, stress, or dietary changes).

Dysbiosis, on the other hand, is an imbalance or disruption in the normal composition of the gut microbiome, potentially leading to inflammation, metabolic disorders, and disease.

While there is no universally ‘healthy microbiome’ signature (one of the major findings of the Human Microbiome Project (HMP)), research has shown that certain patterns – like higher microbial diversity, the presence of key beneficial species, and the ability to perform essential functions (like fibre fermentation or vitamin production) – are often associated with better health outcomes.

And what we eat, how we interact with people, and the activities we undertake all influence the microbiome in both positive and negative ways.

The Role of Microbiota

The bacteria in your microbiome are specifically known as microbiota.

In total you carry about 2-3 kilograms of microbiota in your body, which are constantly being made and excreted (60% of your stool is made up of living and dead microbacteria too).

And these bacteria serve several important functions:

#1 Digesting Food

Gut bacteria can produce enzymes that help us to break down and absorb food.

Bioengineers have even tried using digestive enzymes outside our bodies to more efficiently convert plan biomass to biofuel, which should make the process much cheaper.

What we eat can also change the enzymes these bacteria produce, shaping how effectively we digest different foods and extract nutrients.

For example, a diet rich in complex carbohydrates and fibre can encourage bacteria to produce more enzymes that break down plant polysaccharides, while a high-fat, high-sugar diet may reduce enzyme diversity and shift microbial activity toward less beneficial functions.

#2 Training the Immune System

The science here is still incomplete, but it’s generally accepted that gut bacteria trains our immune system to help fight off infections, viruses, and bad bacteria.

They do this in a special area of your gut called the mucus membrane (the moist inner lining of parts of your digestive tract).

In this zone, your immune cells learn to tell the difference between good and bad bacteria. That way, in the future, your immune system knows which bacteria to attack (the bad ones that can make you sick) and which ones to leave alone (the good ones that help you). This training helps your body stay healthy and avoid attacking helpful bacteria by mistake.

Having said that, most of the studies here have been done on animals, not humans, and there are a number of areas for further research, including how we develop immunity as infants, the connection between the microbiome and specific diseases, and the exact function of specific bacteria in the gut.

#3 Improving Brain Health

Research suggests your gut plays a key role in regulating mood, stress, memory, and even personality.

For example, research done on mice and rats has shown:

- Mice with healthy microbiomes show fewer signs of depression, better memory, and lower stress hormone levels.

- Transferring gut bacteria from shy mice to outgoing mice (and vice versa) reverses personality traits.

- Rats given microbiota from humans with depression develop depressive symptoms themselves.

Though still emerging, human research offers promising findings too:

- One study found that Bifidobacterium bifidum slightly reduced anxiety before a test (especially in sleep-deprived individuals).

- A 2015 study showed that 3–4 weeks of probiotics improved mood slightly.

- Lactobacillus plantarum 299v improved reasoning, memory, and learning in people with depression.

- A 2020 Oxford study linked certain bacterial profiles (Lactococcus, Akkermansia) to higher sociability, while others (Desulfovibrio, Sutterella) correlated with lower sociability.

- Another study showed that people with more diverse gut bacteria reported greater emotional well-being and fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression.

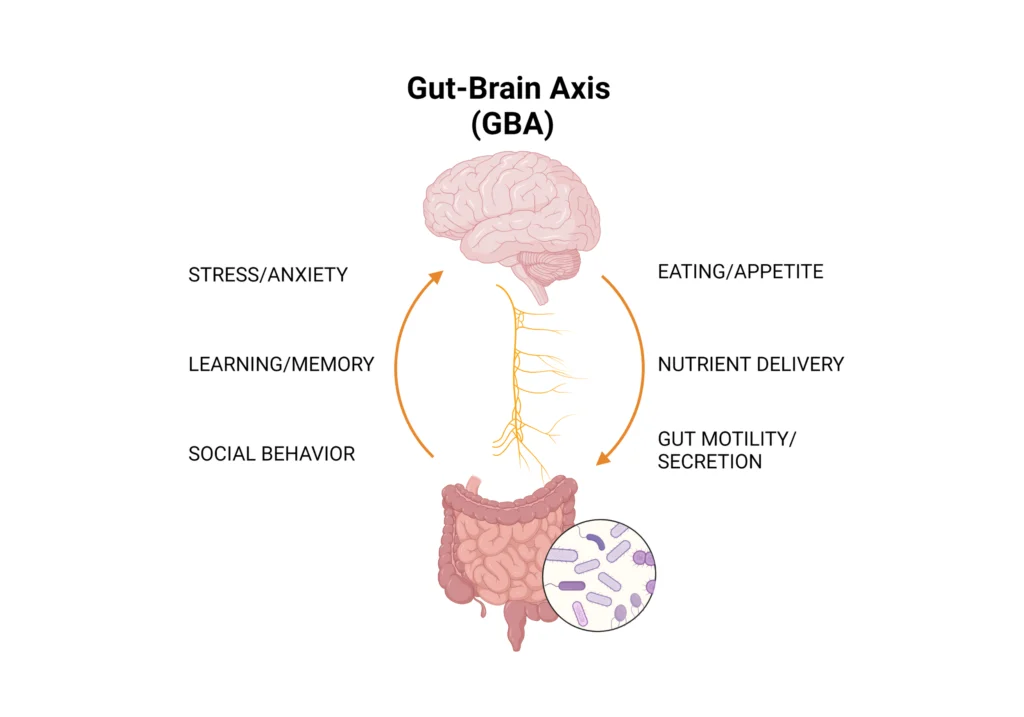

🧠 The Gut-Brain Axis

One of the emerging fields of research in gastroenterology (the study of the gut) is the connection between the gut and the brain.

This is known as the gut-brain axis.

In short, our gut is constantly communicating with our brain and our brain is constantly communicating with our gut.

Direct Neural Signalling

The main way our gut and brain communicate with one another is through a network of nerves that sends signals back and forth.

This communication happens through two main systems: the central nervous system (CNS), which includes the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system (PNS), which connects the rest of the body (including the gut) to the CNS.

One of the key players in this connection is the vagus nerve, a major part of the PNS that acts like a highway between the gut and the brain.

It carries messages in both directions: from the brain to control digestion and from the gut to inform the brain about things like inflammation, nutrient levels, and microbial activity.

What’s fascinating is that gut bacteria can actually influence these signals indirectly too, as we shall now see.

Chemical Signalling

Your brain and gut can also communicate through two key chemical routes:

- Hormones produced by your gut lining.

- Neurotransmitters produced by your gut microbiota.

These signals don’t travel along nerves, but instead move through the bloodstream to reach the brain.

Hormonal Signalling

Hormonal signaling is a slower pathway (minutes to hours) through which the gut communicates with the brain using hormones – chemical messengers released into the bloodstream.

These hormones, including ghrelin, CCK, PYY, and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), influence appetite and feeding behaviour by acting on brain areas:

- Grehlin is a hormone that increases when you haven’t eaten for a while and makes you motivated to seek food.

- CCK (cholecystokinin) and PYY (peptide YY) are released by the gut after eating, signaling fullness (satiety). They tell the brain to slow down or stop eating, counteracting ghrelin’s hunger signals.

- GLP-1 is a hormone produced by neurons in both the gut and the brain, which reduces appetite and inhibits feeding, acting like a brake on eating behaviour. For example, eating food like nuts, avocados, eggs, and high-fibre complex grains increases GLP-1 release, which helps you feel full and less interested in food.

Microbial Neurochemical Signalling

This involves gut bacteria (microbiota) making neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin, and GABA, which travel through the bloodstream to the brain.

Unlike fast neural signals or slower hormonal signals, this is an indirect pathway because it doesn’t use specific nerves but affects the brain broadly by changing its chemical environment.

These neurotransmitters affect your mood, stress, and even behaviour.

- Dopamine: Supported by Bacillus and Serratia bacteria, linked to motivation and mood.

- Serotonin: Supported by Candida, Streptococcus, and Enterococcus, tied to mood, calmness, and social interactions. About 90% of serotonin is made in the gut.

- GABA: Supported by Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, acts like a mild sedative to reduce irritability and anxiety.

The research even suggests that microbiota set the baseline levels of these neurotransmitters. So the overall tide of your mood is likely shaped by the bacteria in your gut.

Specific events (e.g. a compliment or stress) cause quick “peaks” of neurotransmitters via brain circuits, but microbiota provide the steady background level.

Mechanical Signalling

When you eat or drink a lot the physical stretching (distension) of your gut is detected by special neurons called mechanosensors.

If the gut stretches too much, these send signals to your brain (the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ)) to stop eating or, sometimes, to vomit. This is why the CTZ is sometimes nicknamed the ‘vomit centre’.

🧫 Developing and Maintaining Your Gut Microbiome

We begin to develop our microbiomes within seconds of being born.

It’s largely accepted that babies don’t get much, if any, exposure to microbiota inside the womb (although some studies do challenge this). So, we first come into contact with bacteria when we’re born. And the mode of delivery will shape our initial microbiome too.

After that, the first three years of our life are critical to building a diverse microbiome. Some of the key environmental factors are as follows:

- Breastfeeding vs Formula: Breast milk provides prebiotics (e.g. oligosaccharides) that foster beneficial microbes.

- Pets: Exposure to pets introduces environmental microbes, enhancing diversity. One study found that exposure to a pet can decrease the risk of Type-1 diabetes, asthma, and allergies.

- Antibiotics: Early use can disrupt development, altering long-term microbial trajectories.

- Caregivers: Being held by multiple caregivers compared to just one is seen as more beneficial for our microbiome.

By the time you’re three years old you have a basic composition of gut bacteria that will remain relatively consistent throughout the rest of your life.

Although this basic composition doesn’t change, you can still influence the health of your microbiome as you get older.

Building a Healthy Microbiome

#1: Take Prebiotics and Probiotics

Probiotics flood your gut with good bacteria, which help to train your immune system to fight infection and provide you with nutrients.

Many foods contain probiotics (e.g. pickles, yoghurt, kombucha) and they can also be bought in supplement form from the pharmacy.

Prebiotics, on the other hand, feed the good bacteria that are already in your gut. Again, many foods contain prebiotics, such as beans, peas, appleas, and cocoa.

It’s worth noting, however, probiotic supplements are not strictly regulated in many countries. This means products may not contain the strains listed or may not contain viable bacteria at all. So always look for clinically tested strains and reputable brands.

Plus, an excessive intake of probiotics has been linked to the induction of brain fog, so make sure you regulate how much probiotics you take depending on how you feel.

My recommendation is to use low-to-moderate doses for general health, especially from food sources. Then use higher doses antibiotics, during stress, travel, or dietary shifts (but always consult a physician if you’re unsure).

#2: Avoid Bad Bacteria

Most bacteria in our gut is helpful, but some bacteria can make us sick.

Foodborne pathogens like Salmonella, E. coli, and Clostridium difficile can disrupt the gut microbiome and cause acute illness. So make sure you wash fresh produce, cook meat thoroughly, and store food properly.

You should also be cautious of over-sanitising your environment. While basic hygiene is essential, excessive use of antibacterial products and disinfectants can reduce your exposure to the kinds of microbes that help train and strengthen your immune system

[This is sometimes referred to in the context of the “hygiene hypothesis”, which suggests that a lack of exposure to diverse microbes early in life may contribute to higher rates of allergies, autoimmune conditions, and even mood disorders later on].

#3: Take Antibiotics Only When Necessary

Antibiotics are designed to cure bacterial diseases (such as pneumonia) by killing off bad bacteria. This is obviously beneficial when medically necessary.

The problem is that antibiotics also kill good bacteria. So needlessly taking antibiotics (e.g. to treat a cold) depletes the good bacteria in our guts and can even make bacteria immune to antibiotics in the future.

Some scientists say that using antibiotics in our early years is particularly dangerous as our microbiomes aren’t particularly diverse, so small changes to microbiota can have large consequences on the body.

#4: Eat Fermented Food

One of the most effective and natural ways to boost your gut health is by regularly eating fermented foods. These foods introduce live beneficial microbes (probiotics) into your gut and have been shown to increase microbiome diversity and reduce inflammation.

In a landmark study by Dr. Justin Sonnenburg and Dr. Chris Gardner at Stanford University, participants who ate 4–6 daily servings of fermented foods like plain yogurt, kefir, kimchi, sauerkraut, and natto experienced:

- A significant increase in gut microbiota diversity

- A reduction in inflammatory markers (like IL-6)

- Improved immune regulation

Interestingly, the duration of intake mattered more than how many servings were consumed at once. So instead of overloading your diet in one go, try to consistently include a small amount of fermented food each day.

#5: Avoid Processed Food

Modern processed foods are often stripped of nutrients and packed with additives that can harm your gut microbiome.

One major concern is emulsifiers. These are detergent-like compounds added to improve texture and shelf life in many packaged foods. In animal studies, emulsifiers have been shown to disrupt the gut’s protective mucus layer, reduce microbial diversity, and trigger low-grade inflammation.

In addition, the typical Western diet – high in sugar, fat, and ultra-processed foods, but low in fibre – starves beneficial microbes of the fuel they need to thrive.

When you eat a diet rich in complex, plant-based fibre, your gut bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate. These SCFAs help to lower inflammation, strengthen the gut lining, and improve overall metabolic health.

#6: Limit Artificial Sweeteners

The impact of artificial sweeteners on the gut microbiome is still being researched, and while there’s no clear consensus yet, early evidence suggests caution may be warranted.

In animal studies, sweeteners like saccharin and sucralose have been shown to disrupt gut bacteria, leading to altered glucose metabolism and signs of inflammation. However, human data is limited and more research is needed.

Due to the high individuality of the human microbiome, as highlighted by the Human Microbiome Project, some people may tolerate artificial sweeteners better than others. If you consume them regularly, it may be worth experimenting: try reducing them and observe any changes in digestion, mood, or energy.

#7: Support the Foundations of Health

Your lifestyle habits also have a profound effect on your gut health:

- Prioritise quality sleep: Lack of deep, restorative sleep can trigger inflammation and disturb the immune system, which interacts directly with gut microbes. Aim for 6–9 hours of quality sleep each night.

- Stay Hydrated: Proper hydration is essential for healthy digestion, nutrient absorption, and the movement of food and waste through the gut. It also helps maintain the mucus layer that lines your intestines, which acts as a protective barrier for your microbiome.

- Manage Chronic Stress: Chronic stress is one of the fastest ways to disrupt your gut microbiota. It weakens the gut lining, increases inflammation, and alters microbial composition. Incorporate stress-reducing practices like meditation, exercise, and journaling.

- Engage in positive social interactions: Interacting with others – especially in natural or shared environments – can increase your exposure to diverse microbes, which supports microbial diversity. Close friendships, community connection, and even time with pets can positively influence your microbiome by boosting both mood and microbial variety.